Mui Wo reaearcher Jessica Tan provides an overview of the village’s agricultural golden era, 1950 to 1980

In recent years, community projects and grassroots undertakings with local farmers have revealed that Mui Wo possesses a rich agricultural history. Yet, there has been no serious study of this topic to date, which is a gap this research seeks to fill. This article will explain some of the key farming practices adopted in Mui Wo from 1950 to 1980, including the gradual shift from rice to vegetable cultivation at both small, familyrun farms and large industrial farms. It will also reference a change in the Government’s New Territories’ policy in the 1950s, which meant agriculture was promoted as a primary economic activity, encouraged and supported through the establishment of many institutions.

Mui Wo Farming Practices

Like most places in the New Territories, the original inhabitants of Mui Wo traditionally grew rice. Generally, two rice crops were grown each year. According to a 1955 study, when paddy cultivation was still the dominant form of land use in Mui Wo, various types of rice were grown. For the first crop, farmers used Fa Lok Pak (花蘿白) and Fa Yiu Tsai (花腰 仔), as well as Tung Koon Pak (東莞白) and Early Sze Mi (早絲 苗). For the second crop, the main variants were Pak Huk Chai Mi (白殼齊眉) and Wong Huk Chai Mi (黃殼齊眉), with others including Kum Bau Yun (金包銀) and Wong Huk Tsai (黃殼仔).

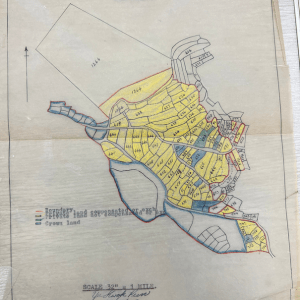

Things started to change when immigrant farmers from mainland China came to Hong Kong following the Second World War, bringing with them vegetable and fruit cultivation techniques. When the indigenous villagers saw the immigrant farmers getting better and more certain returns from growing vegetables, they began to grow vegetables in addition to rice. A 1963 study of Mui Wo land use reveals just how much changed in a decade: in 1953, paddy fields covered 168 acres (77% of available arable land), while vegetables were grown on 42 acres (20% of available arable land). By 1963, only 45 acres of paddy field (30% of available arable land) remained, with 86 acres (57% of available arable land) used for vegetable cultivation.

In the post-war years, there were essentially two different types of farms in place in Mui Wo: family-run farms, which were typically small in size (0.2 to 0.5 acres), and large-scale, industrial farms, which covered several acres.

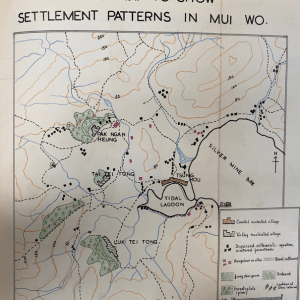

The majority of Mui Wo’s farms were small and family-run, and they were typically located in the older villages, such as Luk Tei Tong, Tai Tei Tong and Pak Ngan Heung. These farms historically relied on all family members, including children, to work the land. At this time, women often gave birth to as many as eight children – with children helping on the farm, there was no need to spend money hiring labourers.

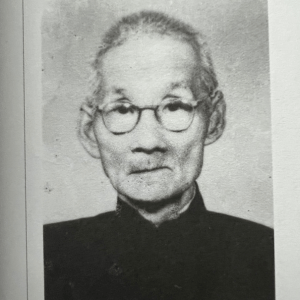

Of the large-scale, industrial farms in Mui Wo, by far the largest was Yu Tak Lee Yuen (裕德利園), owned by Yuen Wah Chiu, a key figure in Mui Wo history, who settled in Chung Hau in the 1930s. Yuen played a central role in the development of Chung Hau and the creation of the Mui Wo Rural Committee. His walled farmhouse built in the 1940s, which we now know as “Yuen’s Mansion,” is a popular tourist attraction and a Grade II-listed historic building.

As of 1963, Yuen’s farm covered 31 acres (185 dou chang), of which 5 acres were devoted to rice growing, 9 acres to fruit and 27 acres to market gardening. The orchard contained 7,000 fruit trees, mostly lychee, with some lemon, guava and wongpei. The field pattern employed was more or less rectangular with an average size of 1 acre (six dou chang), which was very different to the smaller, irregular field patterns maintained by the indigenous Mui Wo families. Yuen’s management-style was also different in that he brought in hired labourers to work on the farm.

Local support for farmers

By far the most important local organisation that supported Mui Wo farmers was the Mui Wo Agricultural Products Marketing and Credit Co-operative Society (Co-operative Society), which was most active from the 1950s to early 1970s. The Co-operative Society was founded in October 1953, with the aim to help Mui Wo farmers sell their vegetables to the quasi-governmental Vegetable Marketing Organisation (VMO), which handled Hong Kong’s vegetable wholesale. The Government felt VMO was needed because middle-men were taking up a large percentage of vegetable farmers’ income.

According to Government reports, the Co-operative Society began transporting vegetables from Mui Wo to the VMO Kowloon wholesale market in 1953, with the aim to minimise farmers’ transport and management costs. Farmers brought their produce, in baskets, to the Co-operative Society for collection each evening. The vegetables were then taken to Kowloon by ferry at around 3am or 4am, so they could be sold early in the morning.

An HKU Department of Geography study found that the Cooperative Society had 115 members in 1964, all of whom paid a HK$10 subscription. The ferry service was terminated on June 1, 1973, as the quantity of vegetables being cultivated in Mui Wo had dropped to a very low level.

The Co-operative Society was of most benefit to the operators of Mui Wo’s larger farms, who had more produce to sell than the owners of Mui Wo’s small, family-run farms. The large farm operators found it viable to accept the relatively lower prices offered by the Co-operative Society in exchange for having their crops transported to the city.

The opposite was true for the Mui Wo family farmers, who grew less produce and did not need to take it to market every day. For them, it made better sense to take their produce to market themselves, where they could sell it at a higher price. Typically, farmers would take the early ferry to Cheung Chau and sell their produce by the ferry pier. But at harvest time, when crops were plentiful, they would work together to transport their vegetables to Hong Kong Island and sell their produce at the Central or Sai Wan markets, which fetched higher prices. In this way, in addition to the formal Co-operative Society, informal village-based farmer networks also existed in Mui Wo, which mostly enabled the smaller, family-run farms to deal with transportation logistics.

Farmers across South Lantau, such as villagers from Pui O or Shui Hau, also had the opportunity to sell their produce to the Co-operative Society and have it transported to the VMO Kowloon wholesale market. However, they struggled logistically. The South Lantau farmers had to bring their produce by road to Mui Wo and by the time they arrived, they would often find the Co-operative Society collection point at capacity – filled by the Mui Wo farmers who had less distance to travel. If the South Lantau farmers did not succeed in selling their vegetables to the Co-operative Society, they would opt to take the ferry and sell their produce in either Cheung Chau or Hong Kong Island, but they would again face the same difficulty of arriving after the Mui Wo farmers.

Institutional support

In addition to the Co-operative Society and local Mui Wo farmer networks, there was also institutional support for the New Territories’ agricultural industry in the post-war era from which Mui Wo farmers benefited. In terms of Government support, one of the Agriculture Department’s main aims was to establish district agricultural stations across the New Territories. The first five sites chosen were Mui Wo, Tai Po, Shatin, Sai Kung, Tsuen Wan and Sheng Shui.

The main role of officers at district agricultural stations was to gain an understanding of local agricultural practices, and demonstrate improved agricultural techniques to local farmers. By 1954, district agricultural stations had become community hubs, constantly visited by farmers. District agricultural officers provided set tours and lectures on different farming topics.

Mui Wo Agricultural Station owned 20 mows of land for demonstration purposes, located behind Choi Yuen Tsuen. However, its lifespan was relatively short – just 12 years from 1951 to 1963. Why the station closed is not clear. According to the Government, the station was closed because it was a vegetable seed producing centre in the heart of a predominantly rice producing area. In contrast, HKU researchers have indicated that the station was abandoned due to labour- and water-access issues. The researchers also noted that the station’s lands had a low yield per mow due to the sandy nature of the soil. In 1955, nearly one acre of land behind the station had to be abandoned, as the crops were often destroyed by wild pigs.

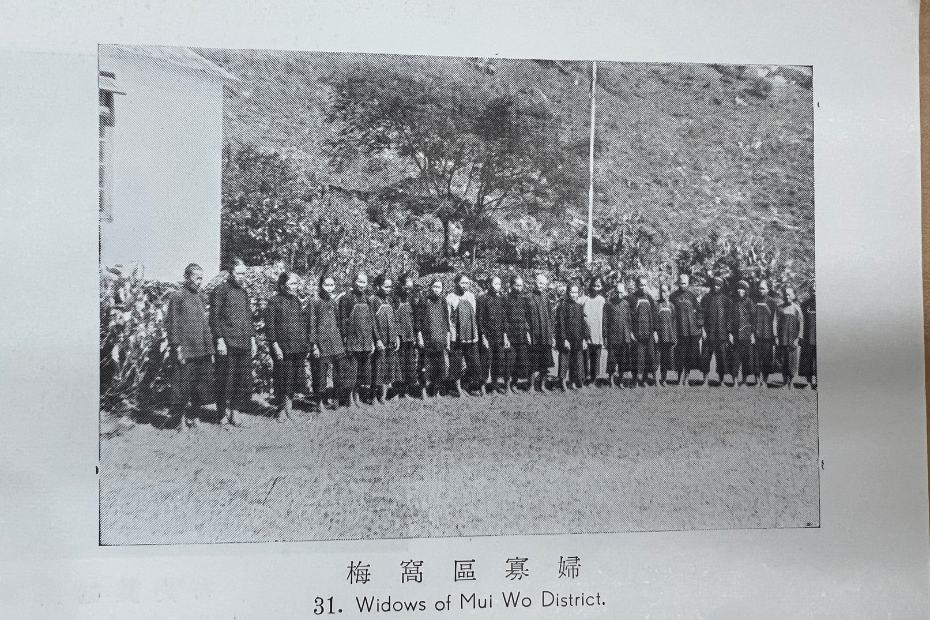

Aside from the Government, the other main provider of institutional agricultural support in the post-war era was Kadoorie Agricultural Aid Association (KAAA). The association was set up by the Kadoorie brothers to help farmers in the New Territories become self-supporting. KAAA sought to do this by providing farming equipment, helping with minor local infrastructure works and distributing cattle to farmer widows in need. KAAA noted that while the Government implemented major infrastructure schemes such as road development, reservoirs and drainage, it was less able to help villagers at the local, grassroots level. As such, KAAA helped create all-weather roads to replace the traditional earth or stone paths within villages to facilitate the transport of produce. In Mui Wo, cement paths were built to connect the farming villages to Chung Hau.

There were also times when the Government and KAAA collaborated, for instance with the New Territories-wide Village Orchard Scheme, which began in 1955. Under the guidance of the Agricultural Department, KAAA provided planting materials and villagers worked together to plant the fruit trees. In Mui Wo, two villages benefited from this scheme – Luk Tei Tong and Pak Ngan Heung. Fruit trees planted included lemon, apricot, tangerine and wongpei.

Gateway to Hong Kong

The best way to understand these complex interactions between different stakeholders in the Mui Wo agricultural community is to view Mui Wo as an “agricultural hub”. Mui Wo was the place where many outside institutions, such as the Agricultural Department and the KAAA, came to set up headquarters and invest in agriculture-related infrastructure. It was also somewhere that large local agricultural institutions, such as the Co-operative Society, were established to benefit farmers throughout South Lantau.

Importantly too, Mui Wo was a hub where South Lantau farmers could purchase agricultural necessities such as fertiliser and farming tools, and sell their agricultural produce. Farmers across South Lantau also benefited from infrastructure improvements in and around Mui Wo, such as the transportation networks, which enabled them to have better access to sales channels for their produce.

After the war, with the re-introduction of regular ferry services to and from Central and the development of the South Lantau Road, Mui Wo began to operate as a “gateway to Lantau,” connecting South Lantau with the urban areas of Hong Kong. This accessibility to Hong Kong Island by ferry made Mui Wo an attractive tourist destination. Just as importantly, it made Mui Wo a “gateway to Hong Kong,” giving South Lantau farmers easy access to the markets on Hong Kong Island, something which facilitated the local agricultural economy and industry for several decades. It is essential to keep this agricultural history and heritage in mind when considering future conservation and development of South Lantau.